Although we encountered two coronavirus outbreaks in recent years (SARS-CoV in 2002 and MERS-CoV in 2012 [still ongoing]), for the vast majority COVID-19 represents our first experience of a global pandemic.

Although it has been over a century since the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, the “fundamental” principles of social isolation and distancing, quarantine, general hygiene particularly hand washing, and face coverings remain our best options for preventing the spread of infection and “flattening the curve”.

A major difference between 1918 and today is that we are in the communication era allowing for anyone with a computer or a phone to express an opinion, and misinformation has been a hallmark of this current pandemic. Misinformation comes in different varieties and levels of severity!

There are essentially three classes of misinformation. The first comes from simple ignorance and not caring. This category includes the conspiracy theorists, anti-maskers, and anti-vaxxers, and mostly these are benign sources of misinformation from unlearned individuals. The second category is more sinister and typically arises from conflicts of interest, and is more politically and economically motivated and dangerous in nature.

For the medical and scientific community, the third category of “misinformation” is most important. It stems from not actually knowing every detail; to be expected with a novel highly infectious disease, and complex pathobiology. Issues such as, imprecise epidemiological curves, speculative timelines for development of antivirals or a widely available safe and effective vaccine, uncertainties regarding disease progression and severity in individuals, are not surprising. Despite these difficulties, it is “the experts” in public health, infectious diseases, and respiratory and emergency medicine that need to be driving the response to COVID-19.

If we were to use the “curve” as an example, there are inherent limitations in developing models of spread. There are too many variables and enormous computing power is required to develop useful predictions. Despite best efforts, expertise, and supercomputers, there will always be a level of discrepancy between the predicted and actual situation. Nevertheless, although not precise, the usefulness of the “good” epicurves is not debatable. So, the third category is not “misinformation” per se, but rather “the best information possible given the circumstances”.

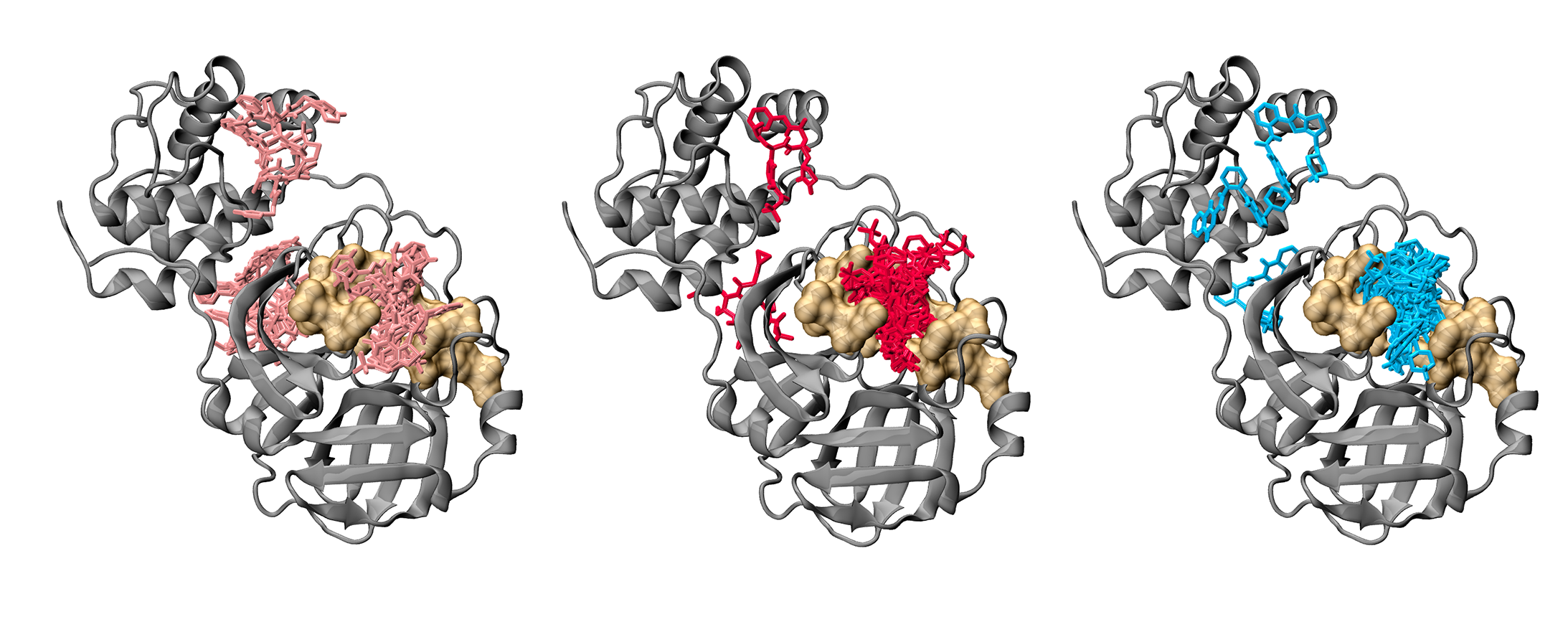

Anyway, supercomputers provide the basis for our contribution to the COVID-19 response. With Dr Andrew Hung (>10 year collaboration) we have been investigating protein-small molecule interactions in models of disease. Together with our senior (Julia Liang), and more recent talent (Eleni Pitsillou), we have been able to pivot quickly and respond to COVID-19. In this context, we are grateful for supercomputing power provided to us from the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre (predominantly), the National Computing Infrastructure (Australia), Spartan High Performance Computing service (University of Melbourne), and the team at Hypernet Labs; Galileo, for enabling cloud computing. The team at Crowdfight COVID-19 was instrumental for enabling us to access the supercomputing facilities.

Similarly, given our >20 year friendship and collaboration with Dr Simon Royce and our long-term team member (>10 years), Katherine Ververis (experts in pathobiology, including respiratory pathology), we are adapting our lung disease models to suit SARS-CoV-2 research. Finally, my expertise in cancer biology and therapeutics has enabled us to initiate programs at identifying and developing potential antivirals.

Of course, medical and scientific progress is inherently slow and incremental and we are realistic that our contributions to the current COVID-19 pandemic will most likely be very modest. We hope that the work we are doing today might add some useful knowledge, and perhaps a foundation for responding to any future incidents.

Until next time … Tranquilo Polymaths.